THE SCOTTISH GREAT KILT

Presented by

MUNGO NAPIER

LAIRD OF MALLARD LODGE

Ceud mile failte! A hundred thousand welcomes! Duncan the Crabby*, Highland troublemaker, at your service, and likely also at your purse. It is my honor to share some history of the Highland great kilt, and to show you its relationship to the modern “wee kilt”. So please, sit back, relax, and let us share the pleasures of that most manly of garments, the great kilt.

The Highland great kilt is an un-tailored garment that wraps around the loins, is belted at the waist, hangs to the knees, and is pleated across the bum, with a generous amount of material above the belt that can be pulled up onto the shoulders. The great kilt is known as the féileadh mór in Gaelic or as the “belted plaide” in Scots English.

(Right) Lord Mungo in full Scottish drag though this outfit is more 17th century than SCA period. The tartan is Campbell, which along with Royal Stewart has become a sort of generic pattern for all of Scotland.

A plaide is a piece of un-tailored woolen cloth used as a mantle or shawl, a blanket, or wrapped around the body and belted as a great kilt. Plaide describes the cloth, and has nothing to do with any decoration or colors we Americans rather erroneously call “plaid”. When decorated, the plaide is sometimes called a breccan.

Tartan today usually refers to the pattern of crossed lines of different colors we know from kilts and other Scottish goods. In the renaissance period, the term described any cloth with colorful Scottish patterns, by then usually all wool. A tartan pattern is more properly called a sett, though this term is seldom used today except by cloth makers and historians.

Let's start with the whole question of when the féileadh mór was invented. The general feeling among kilt enthusiasts is that the great kilt dates to antiquity, and is something the Scots have always worn. Kilt scholars, however, can only point to 1594 for the first verifiable mention of the great kilt. I used to be on the side of the scholars until Lord Wrad of Ce showed me a Pictish carving of two bards wearing the féileadh mór (below). This has caused me to change my viewpoint, at least as far as the Picts are concerned, which pushes the féileadh mór back into the 9th or 10th century.

However, not all Highlanders were Picts. Beginning in the 5th century CE, an Irish Gaelic-speaking tribe known as the Scoti invaded the Hebrides Islands and then spilled over onto the mainland, particularly into Argyle and Bute. It is likely their main garment was the Irish leine. For men this was a linen shirt extending either to mid-calf or mid-thigh. A women's leine extended to the ankles and was more like a chemise, though probably not as well tailored as later English chemises. Leines for both men and women had large bell sleeves like a choir robe. For nobles these were huge, and probably a nuisance (see below), but this was a mark of status. This image shows a highland nobleman from the 1300s who also appears to wear a pleated garment above his waist. This is actually dagging on a short jacket called an ionar. These jackets were tailored garments worn by both Irish and Scottish nobles, and beyond the means of most peasants.

In cold weather both men and women wrapped their upper bodies with a wool mantle or rough cloak known as a plaide. This was similar to the Irish brat, worn by the central figure in the next image. That chap, and the two men to the right, are Irish kerns, elite soldiers often serving as both wingmen and servants to Scottish gallowglass mercenaries in Ireland (the two men to the left). You can spot the kerns by their unique, but really bad haircut, which looks like somebody put a bowl over their heads and cut off everything hanging below the rim. Note that the man is wearing the plaide/brat around his upper body, and it is NOT belted. This is probably how most Hebredian Scots wore the plaide up to near the end of our period of interest. This image dates to about 1521, and by the end of the century, many highlanders were wearing the plaide hanging to their knees, pleated and belted, thus a true kilt.

The first verifiable mention of the great kilt occurs in THE LIFE OF RED HUGH O’DONNEL by Lughaid O’Cleirigh, originally published in 1616. O’Donnell was the Irish Earl of Tirconnaill (now Donegal). In 1594, he hired Scottish mercenaries for another campaign in his perpetual wars to drive the English from Ireland. In modern translation the text says, “Their exterior dress was mottled cloaks of many colours with a fringe to their shins and calves; their belts were over their loins outside their cloaks . . .”

At this point, I'm going to throw up my hands and say, "Wear whatever you want. This is just a game anyway!"

The kilt did not penetrate into the Lowlands until the 19th century. William Wallace, a Lowlander, likely never wore a kilt, despite what Mel Gibson would have you believe (and certainly not that Tarzan-like Hollywood horror from the movie). However, a great kilt on some of his Highland followers in the film might have been possible.

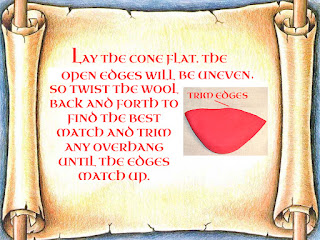

The great kilt is really just a piece of cloth 54 to 60 inches wide and four, five or even six yards long, depending on how much haggis our Scotsman had eaten, and how large his waist and tummy had become. Some people claim the great kilt was nine yards long, but this is absurd, though there is a grain of truth here. Primitive looms of the time could only weave a piece of cloth 28 to 30 inches wide, so the cloth was indeed woven to eight, nine or even twelve yards. Removed from the loom, it was cut into two pieces which were stitched back together side-by-side. Early tartan patterns were simple checks, stripes and tweeds, as the looms lacked a foot treadle needed for more complicated weaves. Most dyes were made from local materials, and the yarns would have often been dyed in muted browns, greens, yellows, black, or natural white. Richer colors like red or deep blue were imported, and were only for the wealthy.

These circa-1630 Scottish soldiers (above) are from the 30 Years War, but are one of the earliest depictions of the kilt. Note the various ways the kilt is worn by three of the men. The musketeer wears tartan "slops".

There were no clan tartans in those early days. A Scotsman wore whatever cloth he could get by purchase, barter or theft (we Scots were great thieves!). However, in isolated glens and on the isles local weavers used the same thread counts and local dyes for generations. Since almost everyone there was part of the same local clan, these weaves were de-facto clan tartans, but without any official status. The first mention of any uniformity comes in the 17th century. Even at the Battle of Culloden in 1746, historians have been able to count only a dozen or so clans that had an "official" tartan. The whole business of clan tartans didn't take off until the early 19th century during the mania for all things "Scotch". Before that time Lowland men would almost never have worn tartan. It was considered uncouth and barbaric. Lowland women, however, seem to have adopted the ersaid, a lovely female version of the great kilt (below).

And what about the "wee kilt" or philabeg (below)? The generally accepted story places its invention at around 1730. Thomas Rawlinson, an Englishman who operated an iron furnace in Glengarie, noted that his workers sweated heavily in their kilts during work. He cut a great kilt in half the long way (or simply unstitched the two halves), and so invented the “wee kilt”. We Scots bristle at the idea of our national dress being invented by an Englishman. Some English also claim to have invented haggis and golf, so this sounds like more cultural imperialism from the south. Thus far, efforts by Scottish researchers to either prove or debunk the Rawlinson story have been fruitless.

But just to toss you another curve ball, take a look at this medieval carving (below) from Paisley Abbey, which seems to show a man wearing a wee kilt (from A SHORT HISTORY OF THE SCOTTISH DRESS by R.M.D. Grange).

The “wee kilt” did become popular in the first half of the 18th century. Not only was it easier to put on, it was cheaper than the great kilt, and could be worn with the English waistcoat (vest) and short jacket that were becoming fashionable.

Evolution of the kilt stopped after the defeat of Bonnie Prince Charlie’s Jacobite rising. In 1747 to break the Scottish spirit, the English banned all tartan clothing for both men and boys. Highland regiments in the English army were allowed to wear the kilt. Some rich and powerful lords on good terms with the Crown were exempt from the law, or were able to flaunt it. The ban was lifted in 1782, but much kilt lore and many tartans had been lost by then.

The Scots at first showed little interest in returning to the kilt. Around 1800 there was a great cultural awakening sparked by the songs and poetry of Robert Burns and novels by Sir Walter Scott. Suddenly everyone wanted to be Highlanders. Even Lowlanders were caught up in the fascination with all things “Scotch”. Sadly, it was now the “wee kilt” to which most Scots turned.

This mania was fueled by the tartan makers, especially Wilson and Sons, who sent salesmen to every clan chief and lord in Scotland. They would ask the chief for a sample of his “clan tartan” and would offer to have the cloth mass produced. If there were no samples, the salesman would examine old family portraits and would pounce on any tartan as the official clan sett. If no tartan was found, the salesman would offer up their sample books and invite the chief to select any still unnamed tartan that looked appealing. Since there were numerous salesmen out at the same time, some setts were chosen by as many as four clans. The Scotts are a canny people, and many knew they were being duped, but few cared -- they were having too much fun playing dress-up.

FOR BIBLIOGRAPHICAL REFERENCES AND KILT VENDORS, PLEASE SEE OUR GENERAL PAGE ON SCOTTISH CLOTHING.

* Duncan the Crabby (or Duncan an Crabbit in Scots) is Lord Mungo Napier's great-grandson and lives about 1590.